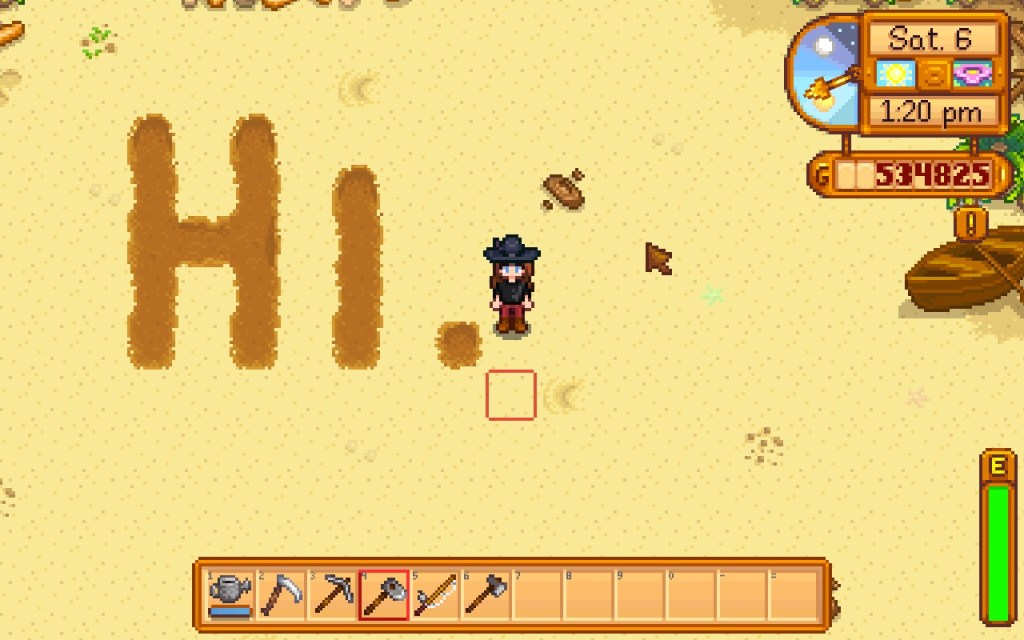

Here’s a continuation of my recent “Everyday Life in Fantasy World”-themed posts. Though, admittedly, Stardew Valley isn’t quite as Fantastical as some of the other recent recommendations.

First of all, welcome to my current recommendation.

Stardew Valley: ConcernedApe and Chucklefish.

You may be wondering what a Greatest Living Author plays when he’s not writing. Well, how about one of the clearest demonstrations of what one person with drive and vision can accomplish?

Honestly, when considered with dispassionate detachment, Stardew Valley is, frankly, an entirely adequate video game. I don’t mean that as negatively as it may sound. The point I’m trying to make is that Stardew Valley is noteworthy for reasons other than just its gameplay.

The really impressive thing about the game is that it was created by one man basically working out of his basement. Yes, Stardew Valley may only be a “good” game, but that one lone man was able to achieve what he did is, honestly, mind-boggling.

If Stardew Valley had ended up as no more than merely functional, it would still be a praise-worthy achievement. But what is especially impressive is that one man has created, with minimal outside help, a game that not only functions technically, but manages to be engaging, engrossing, and interesting is a feat that will not often be repeated.

Entire teams of professionals employed by billion-dollar companies have failed where Stardew Valley succeeds. Now, I’m not naming names, but I’m sure you’ve all got at least one game in mind when I say that.

Stardew Valley is worth playing just for the sake of seeing what one driven person is able to achieve in a passion project.

Incidentally:

And of course, Stardew Valley is worth experiencing for yourself, and not just in a “morbid fascination with a weird novelty” way, either. There is an enjoyable game here. There may not be anything in Stardew Valley that you haven’t seen done better elsewhere, but at the same time, I guarantee you’ve played worse games.

Which, again, is impressive because one guy did all this.

Stardew Valley is, essentially, Harvest Moon for the 21st Century — the series itself is now called Story of Seasons in English due to some complicated legal and licensing issues; as explained in my post about Rune Factory. This is entirely deliberate.

Essentially, it’s a farm life simulator. It’s not quite as simple as that. Stardew Valley is, as far as I can tell, set on a different world than ours, as perhaps indicated by the presence of a wizard (named, shockingly, “Wizard“), monsters that wouldn’t be out of place in a Dungeons & Dragons, um, dungeon, and a race of tiny, circular forest spirits whom the game’s main story arc, such as it is, revolves around helping to restore the fortunes of the town your character moves to.

Now, the Harvest Moon/Story of Seasons series has always had a certain whimsical, fantastic element with characters like the Harvest Goddess and the Sprites.

Photo by fajri nugroho on Pexels.com

All in all, the series basically operates on a level of “real life, with a couple exceptions.”

Stardew Valley is about at the midpoint of Rune Factory and Harvest Moon/Story of Seasons, both in terms of concept — there’s enough fantastical elements to the world that it’s more like “modern day Fantasy world” than “real life with exceptions” — and gameplay. There’s dungeon-crawling like in Rune Factory, though it’s not as interesting or in-depth as Rune Factory, though that’s largely because it’s not the point of the game like it is in Rune Factory.

In literary circles, “Magic Realism” is apparently kind of a loaded term, in part because it’s very connected with Post-Colonial literary movements. So it doesn’t quite fit Stardew Valley, but at the same time, given the aforementioned “real life, with a couple exceptions”, ‘Magic Realism’ probably is the closest real-world word for a genre to fit Stardew Valley — and, for what it’s worth, Tv Tropes does explicitly list Magic Realism on the game’s page.

It’s rather apropos that the game starts with your character quitting his or her job to move to their late grandfather’s farm to escape the bleak, soul-crushing corporate drudgery of office work — that corporations are bad is a recurring theme in the game; the closest thing there is to an antagonist is basically a big box store out to crush small, local business.

Stardew Valley: ConcernedApe and Chucklefish.

Both from your character’s in-game perspective and from a real-life gameplay perspective, Stardew Valley is clearly meant as an escape.

While the game does ostensibly have a goal to work towards (fix the town’s community centre) and a time limit or sorts (you’re evaluated after three in-game years), you can’t lose, you can’t die (if you run out of health in one of the dungeons, you just lose some items and wake up in the town hospital), and that time limit isn’t absolute (after the initial evaluation, you can still play indefinitely and use a few items to get re-evaluated to increase your score).

It’s also incredibly open-ended. Sure, the game points you towards farming as your main source of income, but you could also focusing on mining, or fishing, or exploration. You can get married. Or not. You can work on completing the main story, or any number of side quests. Or not.

Stardew Valley: ConcernedApe and Chucklefish.

It is a bit of a slow burn. You’re starting with basically no money, no stamina, low-quality tools, and a farm in complete disarray. On the other hand, that means there’s a pretty good sense of progression. On the other other hand, you’re going to feel really inadequate once you start looking at other people’s farms — huge amount of crops, multi farm buildings and animals, an hydrological engineering that would put the Cappadocians to shame — and wonder just how in the world they did it.

Again, there’s very little pressure actually put on you by the game itself and ultimately, much as is the case in real life, the most important judge of your own progress and success is yourself.

One of the major cues Stardew Valley takes from Harvest Moon is the system of character relationships. You share the town with a couple dozen over characters with their own likes, dislikes and routines whom you can befriend and, in the case of the eligible bachelors and bachelorettes, marry — shout out to the indisputable best romance option.

Every character has a story arc that progresses as your friendship with them grows and help them work through their issues. And these storylines don’t shy away from serious issues: depression, alcoholism, being your parents‘ unloved other child, escaping from domineering exes, not conforming to your parents’ expectations. The themes are all handled well and never get either too dark and depressing or too saccharine and melodramatic. It’s better writing to deal with serious, real-world issues than you’d see in a lot of games. And again, this was all done by one guy in his basement.

So, to wrap up: Stardew Valley is impressive for being a good game. And it’s especially impressive because that good game was built from basically the ground up by a single person.

It’s a impressive testament to what single person can accomplish with drive and passion, and a good reminder to all the independent artistic-types out there are you can, in fact, find success as an independent artistic-type.

My other recommendations are here.

And you can follow me here:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The author prohibits the use of content published on this website for the purposes of training Artificial Intelligence technologies, including but not limited to Large Language Models, without express written permission.

All stories published on this website are works of fiction. Characters are products of the author’s imagination and do not represent any individual, living or dead.

The realmgard.com Privacy Policy can be viewed here.

Realmgard is published by Emona Literary ServicesTM